How To Find The Key of Any Song By Ear.

Using Burritos.

“Can you taste it?”

I paused, burrito in hand, mouth open. Chris was fond of pulling pranks, but he hadn’t messed with my food. Yet.

“Taste what?”

Chris started laughing “Don’t worry, I didn’t jizz in it or anything. I just put some curry powder in, just to see what it tasted like.”

I took another bite of my burrito. There it was, an unmistakeable hint of curry. Like an ex-girlfriend at a party. It just shouldn’t have been there.

“Don’t quit your day job, Ramsey.”

Chris had just confirmed what I had already known for a long time. Bass players are just the worst.

Chris taught me a valuable lesson that day – Burritos taste weird with curry powder mixed in. When something is a little out in a burrito, you can taste it straight away, but only if you’re used to the particular flavours of a well made burrito. The same idea applies to finding the key of a song – You can find the key to any song, as long as you’re used to the flavour.

This article will show you a method of finding the key of a song by using just the guitar. No humming the tonic like a moron, no guesswork, just a system that uses the pentatonic scale. Also, with this system, you’ll be able to figure out the key of a song in 20 seconds or less.

Just a side note-this method is great for the more harmonically standard styles of music, like rock and pop and country, but it won’t work over jazz or classical music. (BUMMER DUDE)

This method has two steps: Find all possible places where four fret spaces sound consonant on the high e string, and play position 1 of the pentatonic in each of those.

Four fret spaces

Four fret spaces is just a term for me to describe the first two notes of the pentatonic scale. If we’re playing the A Minor Pentatonic scale, the notes on the high e string are 5 8, which have four frets contained in them (5, 6, 7, 8). Thus, we have four fret spaces.

When we don’t know the key of a song, we’ll use these four fret spaces to quickly identify potential candidates for the correct key.

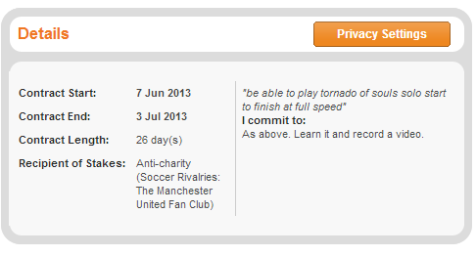

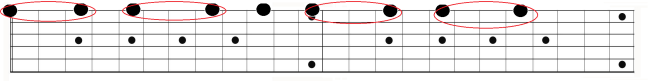

If you look at the pentatonic scale in A Minor on a single string you get this:

If you look you can see two places that have these four fret spaces. Both of these four fret spaces have two notes, both which are consonant. See the diagram below.

Using this method we go from fumbling across the whole Fretboard looking for notes, to identifying two places on the high E string where these four fret spaces are consonant. Once we find these, we can decide which four fret space is pentatonic position one. We’ll talk more about this later, but for now all you have to know is that in any key, there are only two four fret spaces (there are four in the above diagram, but 17 20 is an octave of 58, 1215 is an octave of 03)on the high e string. Also, only one of them will sound right when you play position 1 using them.

Identify the four fret spaces

To find the spaces, play all the possible four fret spaces chromatically, and identify the two positions that are consonant. Do this by going chromatically up the Fretboard: 0 3, 1 4, 2 5, 3 6, etc. I’m just going to throw out a broad definition for consonant here – They’re notes that sound good. I’ll cover this in more detail later.

(Note: you may find up to four of these four fret spaces initially, even without octaves. We’ll weed out the incorrect spaces later).

Play position one of the pentatonic.

Let’s continue with our original example. Let’s say we’ve identified the following four fret spaces, 5 8 and 12 15. All you do now is play position one of the pentatonic in each of these spaces. They will sound very similar, but one will have the unmistakable flavour of the pentatonic and the other will sound a little off. Like a taste of curry powder where there shouldn’t be.

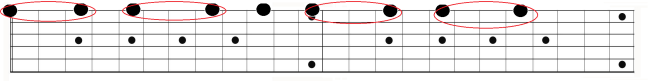

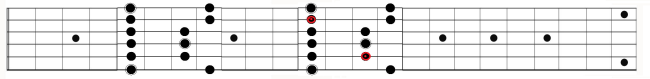

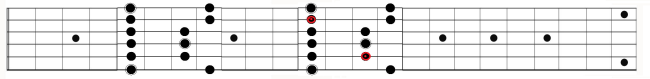

Let’s see what that would look like.

The red highlighted notes are the notes that will sound out of key. Play with these two positions with any backing track in A Minor (YouTube it). The highlighted red notes just don’t sit right like the rest of the notes. The ability to quickly sense the notes that are incorrect is the essence of this technique.

Here’s a full example of this method. Let’s summarise this method before we begin:

1) Use the four fret spaces to locate the two places on the high e string where each note is consonant. Do this by chromatically by moving up the Fretboard: 0 3, 1 4, 2 5, 3 6 etc.

2) When you’ve located the two four fret spaces, play position one in each four fret space. They are only different by one note, as covered above. If you have trouble with this step you need to get used to the flavour of the pentatonic. (More on this later)

So, we’re listening to a song, and we don’t know what key it’s in. Let’s apply the method.

Step One: Play through all the four fret spaces on the high e string, listening out for the four fret spaces that are consonant*. Go up chromatically from 03 to 11 14. When you find four fret spaces where both notes sound correct, write it down. You should end up with 2 ideally, but you may end up with 4. Let’s say you end up with 5 8 and 12 15.

*What do I mean by consonant? I mean both notes sound like they are in key. If you play an F# in A Minor, it’ll sound bad, or out of key. I’m generalising here, and in certain contexts that F# would sound great, BUT when you’re playing the A Minor Pentatonic over an A Minor backing track, F# will sound BAD.

If you’re unsure of whether you understand this concept, try soloing with any song for a few minutes, without using any scales. Can you hear when you play a bum note that’s totally out of key? If you can, with practice this method will work well for you. If you can’t hear the bum notes, there’s help later on in this article.

Step Two: Play position one of the pentatonic on each of these four fret spaces.

Now you’ll have to decide which one of these is the correct key. The more you are used to the flavour of the pentatonic, the easier this will be. They will sound similar, but only one will sound just like the pentatonic should. Note the still highlighted tell tale notes.

Once you’ve decided which of these pentatonic position 1 is, you’ve found the key of your song.

This is the best method I have found for teaching students to find the key of a song in a very short amount of time. Often this method can be well mastered after about two weeks.

I doubt all of you will find it that easy, so here are some common issues and solutions

Common difficulties:

I’m not sure which notes are consonant/correct/good!

If you’re new to improvising this is common. The solution is to get used to the flavour of the pentatonic. Play with a backing track every day, using only position one of the pentatonic scale. It’s hard to hit a wrong note with the pentatonic scale. Soon you’ll hear any ‘out’ notes as loud as a gunshot. A basic way to do this is if the track is in A Minor, play the A Minor Pentatonic. B Minor, B Minor Pentatonic etc. Find millions of backing tracks on YouTube by searching for ‘A Minor Backing Track’ or any variations.

I can’t identify the four fret space notes…

This is usually down to speeding through the 0 3, 1 4, 2 5, 3 6, process. Play all these notes quickly one after another and it all sounds like one big mush.

Think of the correct key of the song as a big old ball of jelly. When you hear notes that are out of key, the ball is stretched. After the ball is stretched you need to let the ball return to its original shape.

Translation: leave 2-5 seconds between each playing of the four fret space. This will allow the key to adjust back to its original ‘shape’.

Should I use the high E string or the low E string?

You can use either, but I prefer the high E string. It is really clear whether the note is in or out.

I’ve identified the two four fret spaces, but I don’t know which one is position one

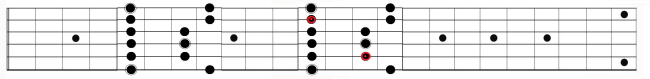

You’re not used to the flavour of the pentatonic yet. Play with one backing track a day, using position one of the pentatonic. Play with backing tracks in a Minor, and really listen to the highlighted notes in the below diagram. Those are the notes that tell you you’re in the wrong spot.

Like I talked about in the burrito example, you need to get used to the flavour of the classic burrito. It’s only when you know the flavour of a classic burrito inside out that you can tell the difference between a classic burrito and a burrito that is just a little bit off.

It’s the same with knowing the flavour of the pentatonic. You need to play the pentatonic with a backing track every day, so that when you’re listening to the pentatonic in very similar positions you can just feel that flavour difference and you’ll know which one is correct.

Action Steps:

1) Play with one backing track a day to get used to the flavour of the Pentatonic

2) Attempt to identify the key of one song you like a day. Give yourself a maximum of two play throughs of the song. Write down your best guess.

3) Sign up for my free ear training course. This course will guide you through everything I talked about in this article in greater detail. The only goal of this course is to be able to identify the key of any song in seconds.

Let’s face it, finding the key of any song is a huge part of any soloists ability. It just can’t be covered in a series of articles, so I invite you to take part in the course here.